The Complete Legal Guide to Transporting a Firearm

By Phillip Nelsen |

Transporting a firearm lawfully through the United States can be an intimidating endeavor. Even the most experienced firearm owners can struggle to comply with the many unique laws that govern possession and transport of firearms from state to state. Although we can’t provide a summary of all the laws relating to firearms, we can provide some key guidance for the following topics:

- A summary of the various layers of law that affect transporting a firearm;

- Transporting a firearm in a vehicle, including on a motorcycle and in an RV;

- Transporting a firearm on a commercial aircraft; and

- Interacting with police officers while armed.

Table of Contents

Types of Law

Although the United States is one nation, we are not governed by only one set of laws. In order to lawfully transport a firearm in the United States there are several layers of laws you must understand and comply with.

Although some of these laws will be specific to one form of transport, most will apply no matter what modality is used to transport your firearm (i.e. vehicle, boat, plane). For example, many recognize the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) regulates commercial air travel, but did you know they also regulate many other forms of transportation, including mass transit, freight rail, highway motor carriers, and even pipelines?

So, exactly how many firearm laws are there in America? The truth is no one knows. Given how frequently firearm laws are modified, and how they are enacted on local, state, and federal levels independently, it’s impossible to accurately calculate a number. Also, what constitutes a law? If one statute prohibits 30 types of conduct, is that one law, or thirty? In 1982, then-president Ronald Reagan stated, “There are some 20,000 gun laws now in the United States.” The NRA frequently cites that number as well, although others have disputed it. Monitoring firearm laws is complicated further by the fact that there are entire cannons of federal laws, called Statutes at Large, that most have never heard of. Statutes at Large are acts and regulations enacted by Congress, which are then classified as public or private laws. Many of these laws are never codified in the United States Code, and instead are simply lumped into non-indexed compilations of law published on the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) website. They are still, however, laws. Tribal lands add another wrinkle. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), there are approximately 574 federally recognized Native American Tribes in the United States. Many of these tribes regulate firearm possession to some degree, but most do not publish their code online.

Regardless of the number of actual laws that exist, the length and complexity of the laws themselves is much more troubling. The amount of reading one would need to do just to become familiar with them all is staggering. Firearm law author Alan Korwin illustrated this point well, when he noted there are approximately 93,354 words contained in federal firearm laws, and an additional 49,442 in Texas firearm laws, for a total of 143,000 words. To put that into perspective, the average novel contains only 40,000 words. This means someone would need to read nearly three novels worth of laws to simply remain compliant, and that’s just for one state.

Although we can’t cover all levels of firearm regulation here, we have included below an overview of the laws regulating the most commonly used modalities.

Transporting a Firearm in a Vehicle

Reciprocity Overview:

Those who have taken a training course to obtain a concealed firearm permit (sometimes referred to as a license to carry, concealed carry permit, concealed weapons permit, and various other names), are likely familiar with the concept of reciprocity. Reciprocity refers to an agreement between states to recognize, or honor, a concealed firearm permit issued by another state. This is sometimes done through formally signed agreements between the states, called reciprocity agreements, and sometimes it is accomplished through state laws.

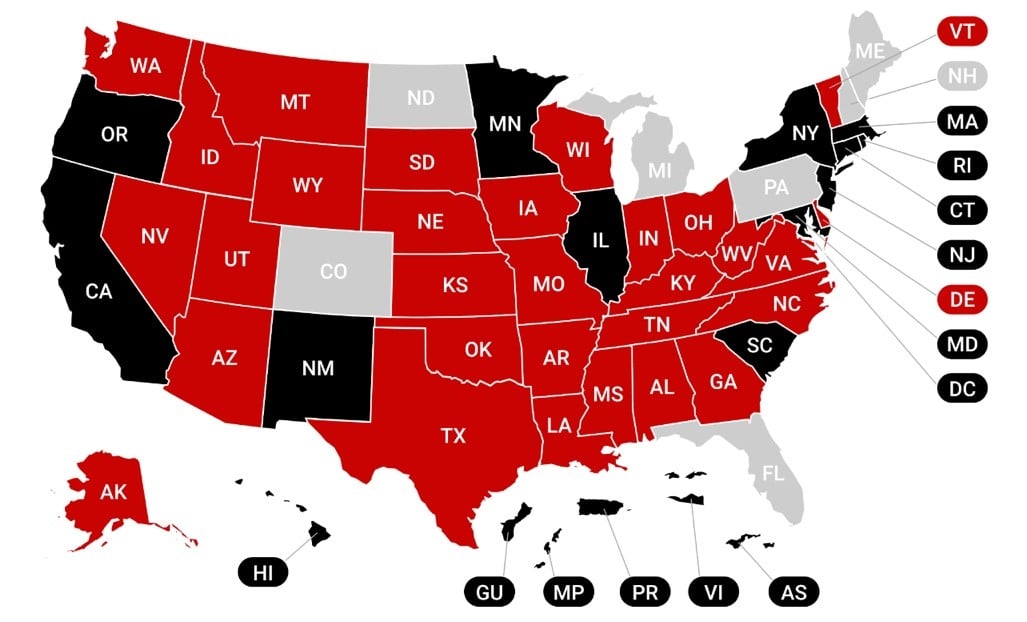

As an example of how reciprocity functions, my Utah Concealed Firearm Permit is currently honored in following red and grey states. The red states honor the Utah permit no matter what state the holder resides in, while the grey states will only honor the Utah permit if the permit holder is a resident of the state of Utah. The grey states are referred to as resident only states.

While in a state that allows you to possess a loaded firearm, either through permit reciprocity or state law, transporting a firearm is significantly easier. If a state honors your permit, you are given much greater flexibility on where and how you can transport your firearm.

However, when in states that do not recognize your permit things can become much more complicated. For purposes of this section, we are focusing on how to transport a firearm through the more restrictive states, such as California, New York, or Maryland.

How A Federal Safe Harbor Law Helps You Transport A Firearm:

As discussed above, no two states have the same laws, and the differences between the states can be dramatic. In 1986, Congress set out to help hunters, travelers and other firearm owners who were getting arrested for merely transporting firearms through restrictive states. To help simplify the complex spiderweb of state firearm laws, Congress passed the 1986 Firearm Owners Protection Act (“FOPA”) as part of Senate Bill 2414. One of the stated functions of FOPA was “to permit the interstate transportation of unloaded firearms by any person not prohibited by Federal law from such transportation regardless of any State law or regulation.” Or, as Senator McCollum explained the law’s purpose at the time it was being debated:

“This [law] is designed to be a "safe harbor" for interstate travelers. No one is required to follow the procedures set forth to section 926A, but any traveler who does cannot be convicted of violating a more restrictive State or local law In any jurisdiction through which he travels. Thus, section 926A will be valuable to the person who either knows he will be traveling through a Jurisdiction with restrictive laws or is unfamiliar with the various laws of the Jurisdiction he will be traversing. Many times people traveling in interstate commerce can unwittingly find themselves in violation of all kinds of technical requirements for possession of firearms. These laws and ordinances vary considerably” 132 Cong. Rec. H4102-04 (daily ed. June 24, 1986).

This specific provision of the law, often referred to as the McClure-Volkmer Rule, provides some protection for gun owners transporting firearms through restrictive states, subject to strict requirements.

The Law (McClure-Volkmer Rule):

Notwithstanding any other provision of any law or any rule or regulation of a State or any political subdivision thereof, any person who is not otherwise prohibited by this chapter from transporting, shipping, or receiving a firearm shall be entitled to transport a firearm for any lawful purpose from any place where he may lawfully possess and carry such firearm to any other place where he may lawfully possess and carry such firearm if, during such transportation the firearm is unloaded, and neither the firearm nor any ammunition being transported is readily accessible or is directly accessible from the passenger compartment of such transporting vehicle: Provided, That in the case of a vehicle without a compartment separate from the driver’s compartment the firearm or ammunition shall be contained in a locked container other than the glove compartment or console. (18 U.S.C. 926A, 27 CFR 178.38.)

Plain Talk Explanation: When traveling through restricted states, such as states that do not honor your concealed firearm permit or otherwise allow you to possess a firearm, federal law still provides a safe harbor for you to transport your firearm in your vehicle, but you need to abide by specific rules. In order to ensure compliance with the above federal law, you must abide by the following five steps:

- You must be able to legally possess the firearm at your place of departure and your place of destination.

- The firearm(s) you are transporting must not be prohibited in the state(s) you are transporting through.

- The firearm(s) must be completely unloaded prior to entering a restrictive state.

- The firearm(s) and ammunition must be stored separately (i.e. separate containers).

- The firearm(s) and ammunition must be stored so they are not readily or directly accessible from the passenger compartment of the vehicle. The unloaded firearm must be in the trunk of your vehicle, if you have a trunk. If your vehicle does not have a trunk, the completely unloaded firearm must be locked in a hard sided container. The firearm may not be in the glove box or center console. Position the locked case as far away from you, in the driver’s seat, as possible. Place the ammunition is a separate location than the firearm, also as far from you in the driver’s position as possible. Only the firearm must be locked in a case, but you can also lock the ammunition in a separate case if you desire.

Remember, if your vehicle has a trunk, both the firearm(s) and the ammunition must be stored in the trunk, recommended in separate containers. If your vehicle does not have a trunk, then your firearms must be in a locked hard-sided container, and both the firearm(s) and ammunition must be stored as far from you in the driver’s seat as possible.

Once the above 5 steps have been satisfied, you are entitled, under federal law, to lawfully transport a firearm in your vehicle through a restricted state. Some states do not require you to complete all of the above steps, but some do. New York, Maryland, New Jersey and California, for example, are responsible for nearly every case on the books dealing with this law, and those states often prosecute gun owners aggressively. To ensure you are given safe harbor, make certain you always follow these 5 steps.

Finally, this law only provides safe harbor while actively transporting firearms/devices that are not otherwise prohibited in the restrictive state. This means you will need to know what firearms/devices are prohibited in the states you are traveling through, and you will also need to be careful that you are only transporting, and not vacationing, in the restrictive states. These two issues are covered in more detail below.

What About Transporting High Capacity Magazines, Silencers, “Assault Weapons” or Other Prohibited Items Through A State?

It is important to understand that, although this federal law allows you to transport some firearms through restrictive states, it does not allow you to transport items that are prohibited under state law, such as “high-capacity magazines” or “assault weapons” (as these terms have been defined by restrictive states). In one of the few cases that addressed this specific question, the court ruled that the federal law discussed above does not prohibit states from enforcing bans on large capacity magazines or bans on other weapons, like “assault weapons”. Specifically, the court warned that:

The risk that a person transporting firearms in accordance with [the federal safe harbor law] will be arrested in New Jersey for possessing an illegal firearm or magazine is the same risk that person encounters whenever he or she drives through a state where such weapons are illegal. (see Coal. of New Jersey Sportsmen v. Florio, 744 F. Supp. 602, 610 (D.N.J. 1990)).

Meaning, if the item you are transporting is prohibited in the state through which you plan on transporting it, the federal law discussed in this section will not protect you. As such, it is essential that you know the laws of the states through which you will be transporting your firearms. (also see State v. Rackis, 333 N.J. Super. 332, 755 A.2d 649 (App. Div. 2000).

How Long Can I Be In A State And Still Be Considered “Transporting“?

Remember, this is a transport law, not a vacation law. If you are visiting a restricted state for a prolonged period of time, such as a vacation, the federal law discussed in this section will not offer you safe harbor. You will need to verify what is required by the state where you will be visiting prior to transporting your firearm to a restrictive state for a prolonged stay.

So how long can you be in a state and still be considered “transporting”? There is no solid answer to this question, as the law does not provide a time threshold. In one of the only cases dealing with this specific question, a man named Paul Guisti was arrested for having an unloaded .45–caliber pistol in a locked safe, inside the living quarter of his boat. At the time of his arrest, he was navigating in the waters just off shore from New York. Paul had skippered his boat from his home in Florida, along the eastern seaboard to New York, and then planned on returning to Florida, prior to being arrested. Given that Paul was acting as more of a tourist than a transporter while in New York, federal law did not protect him from prosecution. While upholding Paul’s conviction, the court noted Paul was not transporting his gun interstate, but rather, admitted he was traveling along the Eastern seaboard and docking in various states for undefined periods of time. This is more of a tourist activity. The court reasoned as follows:

The Court is not persuaded that [18 USC § 926A] applies to interstate travel which is in actuality a round-trip foray with a gun into states that the defendant is not entitled to possess the gun. The plain language of the statute mandates application only if the defendant was transporting the gun from one state to a different state. (See People v. Guisti, 30 Misc. 3d 1229(A), 926 N.Y.S.2d 345 (Crim. Ct. 2011)).

Although it doesn’t provide a clear answer of what timeframe would be considered transporting, it is clear the courts will look into the facts of each case to determine if you are a tourist or a transporter. In other words, if you plan on visiting Disneyland, staying multiple days to see the sights, or doing other tourist related activities, you should not plan on having the protection of federal law.

What About Vehicles Without Trunks, Like Single-Cab Pickups or Motorcycles?

There are no known court cases addressing specific vehicle types. Congress did include an exception for vehicles lacking a trunk, such as pickup trucks or motorcycles. For these, the firearm must “be contained in a locked container other than the glove compartment or console.” While debating how exactly someone should transport the firearm on their motorcycle, the Senate records state:

It is anticipated that the firearms being transported will be made inaccessible in a way consistent with the mode of transportation–in a trunk in vehicles which have such containers, or in a case or similar receptacle in vehicles which do not. (See S. Rep. No. 476, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 25 (1982))

It is the clear intent of the Senate that State and local laws governing the transportation of firearms are only affected if—first, an individual is transporting a firearm that is not directly accessible from the passenger compartment of a vehicle. That means it cannot be in the glove compartment, under the seat, or otherwise within reach. The only exception to this is when a vehicle does not have a trunk or other compartment separate from the passenger area. The weapon must be contained in a locked container other than the glove compartment or console… Any ammunition being transported must be similarly secured. 132 Cong. Rec. S5358-68 (daily ed. May 6, 1986).

Because the law is not explicitly clear, the best available advice is to make the firearm as inaccessible as possible to you in the driver’s or rider’s position, ensuring that the firearm you are transporting is locked inside a hard-sided container and the ammunition is stored separately from the firearm.

Police Encounters While Transporting a Firearm

If you are stopped by a police officer while carrying or transporting a firearm, are you required to tell the officer? Even if you aren’t required to do so, should you tell the officer? The answer to this question will depend on what state you are in at the time you are stopped. This is due to the fact that there are 3 different categories of police encounter states, we call them Duty to Inform States, Quasi Duty to Inform States, and No Duty to Inform States.

Some states impose a legal duty upon permit holders that requires them to inform a police officer of the presence of a firearm whenever they have an official encounter (such as a traffic stop). These states are called “Duty to Inform” states.

Duty To Inform States:

In these states you are required by law to immediately, and affirmatively, tell a police officer if you have a firearm in your possession. As a quick reference, the duty to inform states at the time of publishing this article are as follows:

- Alaska (Alaska Stat. Ann. §11.61.220)

- Arkansas (Ark Admin. Code 130.00.8-3-2(b))

- Maine: (Permit holders have a quasi duty, non permit holders have full duty to inform).

- Michigan (MCL 28.425f(3))

- Nebraska (Neb. Rev. Stat. §69-2440)

- North Carolina (N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. §14-415.11)

- Oklahoma (Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21, §1290.8)

- South Carolina (§23-31-215)

- Texas (must provide permit when asked for ID, §411.205)

- Washington D.C. (Title 7 Subtitle J Chpt. 25 § 7-2509.04)

If you find yourself in one of the duty to inform states you must affirmatively inform an officer if you have a firearm. Failure to inform the officer while in one of these states can result in a criminal charge and suspension of your carry permit. As an example of what a duty to inform law looks like, consider what Michigan’s law requires:

An individual licensed under this act to carry a concealed pistol and who is carrying a concealed pistol or a portable device that uses electro-muscular disruption technology and who is stopped by a peace officer shall immediately disclose to the peace officer that he or she is carrying a pistol or a portable device that uses electro-muscular disruption technology concealed upon his or her person or in his or her vehicle. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 28.425f

When informing an officer that you have a firearm in your possession, we recommend following these four steps:

- Keep your hands visible at all times. If you are in a vehicle place your hands on the steering wheel until you have informed the officer of the presence of the firearm, and fully complied with his or her instructions.

- Advise the officer that you have a valid concealed firearm permit and there is a firearm in your vehicle/possession.

- Advise the officer of the location of the firearm.

- Comply fully with all instructions given by the officer. Do not reach for your weapon, your permit, or do anything that might be interpreted as reaching for your weapon. Keep your hands visible unless instructed to do otherwise.

Quasi Duty To Inform States:

In addition to the above duty to inform states, some states have quasi duty to inform laws. These laws generally require that a permit holder have his/her permit in their possession, and surrender it upon the request of an officer. The specific requirements of these laws will vary from state to state. It is important to note that being required to give an officer your permit once it is asked of you (quasi duty to inform), and being required to affirmatively tell an officer you have a firearm without being prompted (duty to inform), are two very different legal requirements.

As an example of what a quasi duty to inform law looks like, consider what Iowa’s law requires:

A person armed with a revolver, pistol, or pocket billy concealed upon the person shall have in the person's immediate possession the permit and shall produce the permit for inspection at the request of a peace officer. Failure to so produce a permit is a simple misdemeanor. Iowa Code Ann. § 724.5

As you can see, unlike Michigan’s law, Iowa does not require you to immediately and affirmatively inform the officer you have a firearm, but instead you must simply produce your permit for inspection upon request of the officer.

No Duty To Inform States:

The final category of states are classified as no duty to inform states. In these states there are no laws that require a gun owner to affirmatively inform an officer if they have a firearm. Additionally, there are also no laws that require them to respond, or provide a permit, if asked about the presence of a firearm. A few questions arise when we discuss no duty to inform states.

Are You Required To Respond When Asked About Firearms?

It is important to note that if you are in a no duty to inform state, failure to inform an officer, or respond when asked if you have a firearm, does not constitute probable cause to search a vehicle (see United States v. Robinson, 814 F.3d 201, 210 (4th Cir. 2016)). In fact, the courts have repeatedly held that a person who is approached by a law enforcement officer is free not to entertain the encounter when the officer does not otherwise have an adequate basis to detain or arrest the person. An unwillingness to communicate with law enforcement is not a basis to initiate a detention under Terry. (see Florida v. Bostick, 501 U.S. 429, 437 (1991)).

What Are Stop & Identify Laws?

Even if you are not legally obligated to inform the officer of your firearm, that doesn’t mean you are not legally required to communicate other information to the officer, such as your name or date of birth. At the time of this publishing, 25 states have stop & identify laws. These laws authorize police to lawfully order people whom they reasonably suspect of committing a crime to state their name, and sometimes provide photo identification or their date of birth. These laws do not, by themselves, necessarily require the disclosure of firearms. As an example of how these laws function, consider Utah’s stop and identify law:

A peace officer may stop any individual in a public place when the officer has a reasonable suspicion to believe the person individual has committed or is in the act of committing or is attempting to commit a public offense and may demand the individual’s name, address, date of birth, and an explanation of the individual’s actions. A person is guilty of failure to disclose identity if during the period of time that the person is lawfully subjected to a stop:

- (a) a peace officer demands that the person disclose the person’s name or date of birth;

- (b) the demand described in Subsection (1)(a) is reasonably related to the circumstances justifying the stop;

- (c) the disclosure of the person’s name or date of birth by the person does not present a reasonable danger of self-incrimination in the commission of a crime; and(d) the person fails to disclose the person’s name or date of birth

Although it is not the focus of this article, if you desire to be fully informed about police encounter laws, you should verify each particular state’s stop and identify law prior to traveling.

Even If Not Required, Should You Inform An Officer Of Your Firearm?

Knowing that one is generally not required to inform an officer in no duty to inform states, the question often arises as to whether one should inform an officer. The answer is…maybe. Obviously, it is highly encouraged to be courteous and respectful at all times when interacting with law enforcement. However, there are a few points of consideration related to informing an officer about a firearm that you should be aware of.

First Point of Consideration: Waiving Your Fourth Amendment Rights

Many gun owners have a natural tendency towards informing an officer that they have a firearm. After all, if you’ve gone through the process to obtain a permit or research the laws related to transporting a firearm, you are law abiding by definition, right? That may be true, but a potential outcome of informing an officer that you have a firearm is that the officer might then have the ability to perform what is called a Terry Stop or a Terry Frisk. The Terry Doctrine stems from a 1968 Supreme Court case, Terry v. Ohio. In Terry, the United States Supreme Court held that an officer may perform a protective frisk and search pursuant to a lawful stop when the officer reasonably believes a person is “armed and presently dangerous to the officer or others” (see: 392 U.S. 1, 24, 88 S.Ct. 1868, 20 L.Ed.2d 889 (1968)). This also gives the officer authority to temporarily disarm the permit holder “in the interest of officer safety.” The Court did caution that a search “is a serious intrusion upon the sanctity of the person” and should not be taken lightly. Still, the basis for the search itself is largely left up to the officer’s discretion once he is made aware of the presence of a weapon.

The sole purpose for allowing the frisk/search is to protect the officer and other prospective victims by neutralizing potential weapons (see: Michigan v. Long, 463 U.S. 1032, 1049 n. 14, 103 S.Ct. 3469). As an example, a Terry Stop allows a police officer to remove you from your vehicle, pat down all occupants of the vehicle (using the sense of touch to determine if they are armed), as well as search the entire passenger compartment of the vehicle including any locked containers that might reasonably house a weapon. In other words, telling a police officer you have a firearm on you or in your vehicle can serve as a waiver of your Fourth Amendment rights and allow the officer to conduct a warrantless search.

This issue was recently highlighted in a 4th Circuit Court of Appeals case United States v. Robinson. In Robinson, the court extended the Terry Doctrine further than it previously had. In its ruling, the court ruled that not only does disclosing a firearm serve as a waiver of your fourth amendment rights, but also because firearms are “categorically dangerous”:

an officer who makes a lawful traffic stop and who has a reasonable suspicion that one of the automobile’s occupants is armed may frisk that individual for the officer’s protection and the safety of everyone on the scene… It is also inconsequential that the passenger may have had a permit to carry the concealed firearm. The danger justifying a protective frisk arises from the combination of a forced police encounter and the presence of a weapon, not from any illegality of the weapon's possession. United States v. Robinson, 846 F.3d 694, 696 (4th Cir. 2017)

As Judge Wynn ominously wrote in his concurring opinion to that case, “those who chose to carry firearms sacrifice certain constitutional protections afforded to individuals who elect not to carry firearms.”

Although it may seem inconsequential, the waiver of your Fourth Amendment rights can have significant consequences, as illustrated by the next point of consideration.

Second Point of Consideration: You Are Probably A Criminal, You Just Don’t Know It …Yet.

You are probably a criminal. We all are from time to time. As mentioned previously, we don’t even know how many gun laws there are in America, which means it is virtually impossible to know if you are complying with all of them simultaneously. Knowing this, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson once said, “any lawyer worth his salt will tell [his client], in no uncertain terms, to make no statement to the police, under [any] circumstances.” The reasoning behind Justice Jackson’s statement isn’t because police officers are bad, it is simply because the average civilian has no idea how many laws they may be breaking at any given time. As a former prosecutor, and later as a defense attorney, I deal with clients routinely that are charged with crimes they had no idea they were committing at the time. As the saying goes, ignorantia juris non excusat… ignorance of the law excuses not.

Here is one example of how the I have nothing to hide mentality can land you in hot water. Let’s imagine you are a Utah resident, and a Utah concealed permit holder. Your Utah permit is valid in well over 30 states, so you decide to take a road trip with your firearm. As you’re driving through Idaho, where your permit is valid, you get pulled over for speeding in a school zone. Because you are an upstanding citizen and you have nothing to hide, you immediately inform the officer that you have a firearm in the vehicle…and now you’ve confessed to a felony. Wait, what? How did that happen? Let’s review.

18 U.S.C.A. § 922(q)(2)(A), otherwise known as the Federal Gun-Free School Zones Act (GFSZA), states that:

It shall be unlawful for any individual knowingly to possess a firearm that has moved in or that otherwise affects interstate or foreign commerce at a place that the individual knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a school zone.

The term “school zone” is defined by 18 U.S.C.A. § 921 as in, or on the grounds of, a public, parochial or private school; or within a distance of 1,000 feet from the grounds of a public, parochial or private school. The term “school” means a school which provides elementary or secondary education, as determined under State law.

There are a few narrow exceptions to this law, one of which is:

if the individual possessing the firearm is licensed to do so by the State in which the school zone is located or a political subdivision of the State, and the law of the State or political subdivision requires that, before an individual obtains such a license, the law enforcement authorities of the State or political subdivision verify that the individual is qualified under law to receive the license.

Remember, you have a permit from Utah which is valid in Idaho, but was not issued by Idaho. This means federal law is in full force against you. The potential penalty for violating this law is five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. If you would like more details about this issue, you can read the ATF’s analysis of it here.

Of course, as is often the case, the Idaho officer may sympathize that you are not intending to violate federal law, and may choose not to escalate the situation beyond a mere traffic citation. Millions of people violate the federal GFSZA every year, and few are prosecuted. Given the potential life changing penalties, however, it’s certainly something to keep in mind. It is also only one of many examples of how a gun owner might find themselves inadvertently violating the law.

In summary, it is not my intent to tell you how you should interact with law enforcement, or imply in any way that law enforcement should be treated disrespectfully or that they are out to get gun owners. Police officers, by and large, support the shooting sports community and are members of it themselves. I strongly encourage everyone to treat law enforcement with respect. With a proper understanding of the law, however, you can treat someone respectfully without waiving your constitutional rights.

Transporting a Firearm on a Commercial Aircraft

Each year the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) catches approximately 4,500 firearms at checkpoints in commercial airports. The vast majority of these firearms are accidentally, or negligently, transported. If you are planning on traveling with your firearm through a commercial airport it is essential to know how to do so lawfully. Below we will discuss the steps required to transport a firearm and ammunition, with instructions for before departing as well as once you arrive.

Transporting A Firearm

Instructions Prior to Departing for the Airport:

- All firearms, firearm parts (including magazines, clips, bolts and firing pins), replica firearms - including firearm replicas that are toys - are prohibited in carry-on baggage. As such, you must transport all of these items in checked baggage only. Rifle scopes, however, are permitted in carry-on and checked baggage.

- Firearms must be unloaded. Remove the magazine from any firearms even though the magazine may be unloaded. Under federal law (49 CFR 1540.5) a firearm may be considered “loaded” if the firearm has a live round of ammunition, or any component thereof, in the chamber or cylinder or in a magazine inserted in the firearm.

- The firearms must be locked inside a hard-sided container. The container must completely secure the firearm from being accessed from any side. Locked cases that can be easily opened, or pried open on any side, are not permitted. Be aware that the manufacturer’s container the firearm was purchased in may not adequately secure the firearm under these regulations.

- You may use any brand or type of mechanical lock to secure your firearm case, including TSA-recognized locks. You are not, however, required to use TSA branded locks.

- The checked suitcase does not need to be locked, although it is advisable, but the case containing the firearm must be locked. You may check your encased firearm inside of a larger suitcase, or as its own checked baggage.

Instructions Upon Arrival at the Airport:

- Immediately make your way to the baggage check counter, you may not use a kiosk or self-service checking service to check your luggage.

- Upon arriving at the counter, verbally declare that you have a firearm in your suitcase. “I have an unloaded firearm locked in a case inside this piece of checked luggage” or similar statement will suffice.

- The airline employee will then ask you to sign a certification declaring under penalty of federal law that the firearms are unloaded and locked inside a hard sided case. That signed certification, generally in the form of an orange 3x5 card.

- The airline will then direct you on how TSA will process your luggage. This may involve a manual TSA inspection, or an electronic scan, but generally will not take more than fifteen minutes.

- Only you should retain the key or combination to the lock unless TSA personnel request the key to open the firearm container to ensure compliance with TSA regulations. If the key is requested, it should be returned to you upon completion of the inspection.

- TSA will then take custody of your firearms and you may proceed to the security checkpoint.

Keep in mind, bringing an unloaded firearm, ammunition, or even replica firearms to the security checkpoint all have potential criminal and civil penalties/fines. Once you enter the secure checkpoint queue (the line), the crime has already been committed.

If you are traveling internationally with a firearm in checked baggage, please check the U.S. Customs and Border Protection website for information and requirements prior to travel.

Relevant Statute: Title 49: Transportation – Part 1540- Civil Aviation Security – §1540.111 Carriage of weapons, explosives, and incendiaries by individuals

Transporting Ammunition

Ammunition is prohibited in carry-on baggage, but may be transported in checked baggage. Firearm magazines and ammunition clips, whether loaded or empty, must be securely boxed or included within a hard-sided case containing an unloaded firearm.

Ammunition may be transported in the same hard-sided, locked case as a firearm if it has been packed as described above. You cannot use firearm magazines or clips for packing ammunition unless they completely enclose the ammunition. A round of ammunition will not be considered exposed if it has an exposed primer. Firearm magazines and ammunition clips, whether loaded or empty, must be boxed or included within a hard-sided, locked case.

Small arms ammunition, including ammunition not exceeding .75 caliber and shotgun shells of any gauge, may be carried in the same hard-sided case as the firearm.

How To Stay Up To Date On Firearm Laws:

We hope this transportation guide has been useful to you. Legal Heat offers a completely FREE 50 state guide to firearm laws mobile phone application called “Legal Heat”. They also offer a variety of online and in-person training classes on concealed carry, firearm law, firearm safety, and much more.

About Phil Nelsen:

Phil Nelsen is a nationally recognized firearm law attorney, expert witness, tenured college professor, author, and co-founder of Legal Heat - one of the nation’s largest firearms training firms. Legal Heat offers concealed carry and other firearm training classes nationwide, and has certified over 400,000 students to obtain carry permits. Phil is the author of Legal Heat: 50 State Guide to Firearm Laws and Regulations which can be downloaded in app format on iTunes, GooglePlay and Kindle App stores. You can purchase the paperback version of the Legal Heat 50 State Guide or sign up for a class by visiting Legal Heat's website.

About Legal Heat:

Founded in 2008, Legal Heat has grown to be one of the largest firearm training firms in America. Operating in nearly every state, Legal Heat has certified over 400,000 students to obtain their carry permits. In addition to carry permits, Legal Heat also publishes the industry leading Legal Heat: 50 State Guide to Firearm Laws and Regulations, which is available in both app and traditional book format. Beyond concealed carry certification courses, Legal Heat offers a number of additional online and in-person training courses tailored to everyone from beginners to experts. To view a list of available courses, visit Legal Heat online at www.legalheat.com.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is not to be construed as legal advice or acted upon as if it is legal advice: it is provided for informational and entertainment purposes only. While we strive to provide accurate, up-to-date content, we cannot guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the information. Gun laws can change frequently, especially at the state and local levels. Application of gun laws can be unique to an individual’s situation. We recommend that each individual consult with a competent and qualified legal professional before purchasing, transporting, or using any firearm or firearm-related product.

Last updates: 4/26/2023